How to Hike the Narrows

A once-in-a-lifetime trek through the world-famous Zion slot canyon turns into scrambling for high ground in an unexpected downpour.

July 9th started the way most big adventure days do: a pre-dawn wakeup, hot coffee, and stress about whether or not I’d be able to poop before we got on the trail.

Two days earlier, I’d gotten the news that we scored last minute permits to hike the entirety of the Narrows in Zion National Park from top to bottom. While anyone can hike the lower section of the Narrows without a permit, only forty people get to enter the top of the canyon each day.

The eighteen mile trek promises a wilderness experience like no other, and LNT practices are strictly enforced. This means carrying out everything, including human waste — hence my poop stress.

One thing slot canyons are infamous for are their dramatic and unpredictable flash floods. Just a week prior to our trip, the worst flash flood in fifty years swept through Zion, washing away roads, tents, and cars. Needless to say, we were checking the forecast every day leading up to the trip and saw nothing but blue skies ahead.

One final glance at 5:00am the morning of departure confirmed no rain or flash flooding was expected. We started hiking at 7:30am in bright sunlight, 18 miles of slot canyon ahead, and one lonely puff of white cloud overhead.

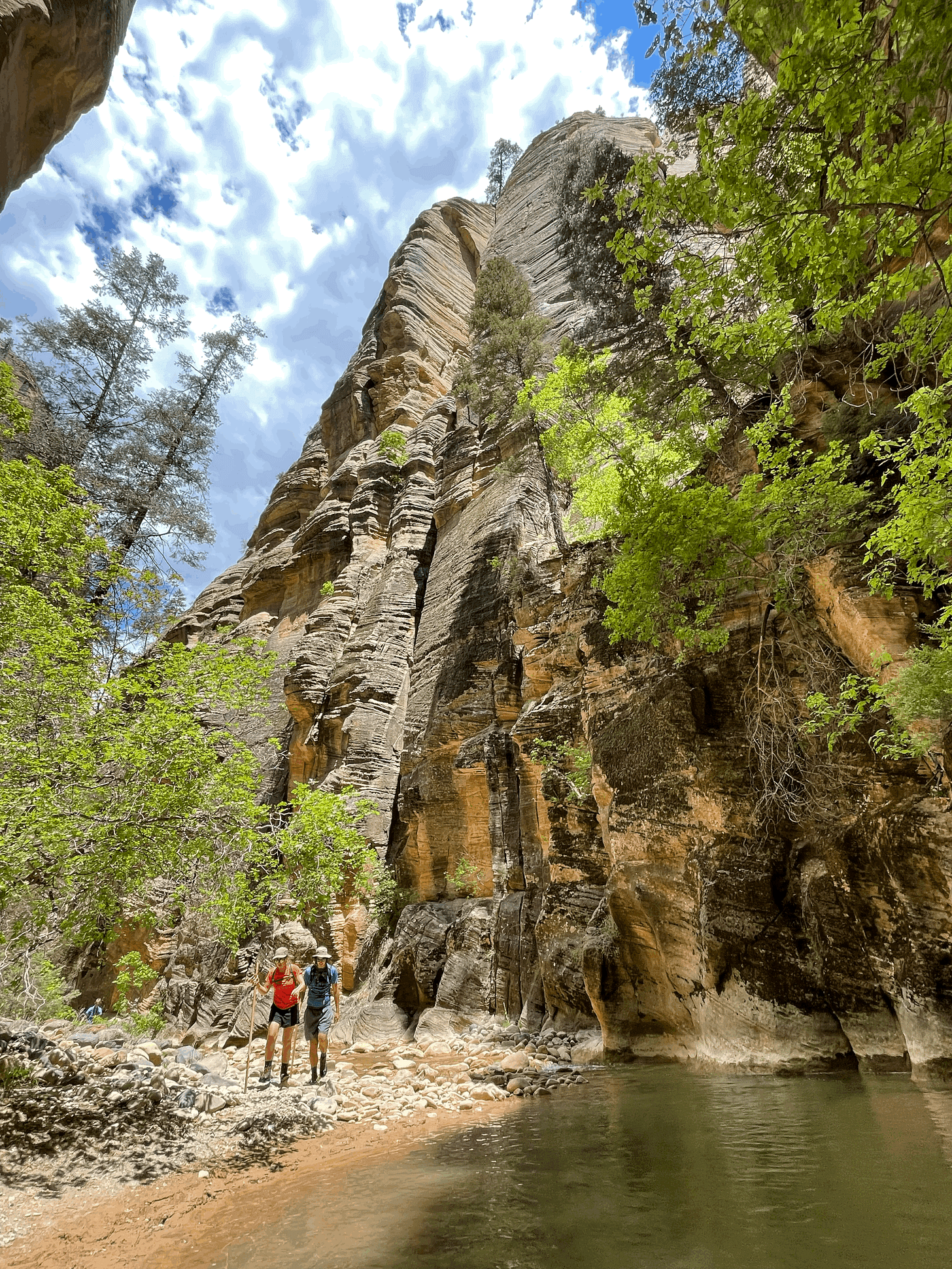

The Narrows is a river walk through time. You begin alongside meadows atop the Colorado Plateau and mile by mile wind your way downward through eons of Navajo Sandstone. In another million years, the canyon won’t exist anymore. The river will have eaten away the layers of stone, one and three quarters of an inch every thousand years, until the high-country meadows of today are finally eroded into the dramatic slot canyons of tomorrow, and the slot canyons of today are lost forever to time.

Lush forest gives way to larger and taller canyon walls until, as if by magic, the plateau is a thousand feet above our heads, perched atop looming sheets of ancient sandstone.

At lunch, we couldn’t help but notice that the one, small, solitary white puff of cloud in the sky had grown considerably less small and notably less solitary.

The white puffiness bordered a deeper gray center. If I had to guess, it looked like a storm cloud, but it’s hard to decipher any weather patterns from the bottom of a canyon where only a sliver of sky is visible.

Needless to say, we picked up the pace a bit and covered the next five miles to Big Spring in good time, my fiancé Nicole leading the charge. She’d heard enough horror stories of flash flooding to know she didn’t want to be anywhere near a slot canyon in the rain.

After a few hours, we arrived at Big Spring, the furthest point up the canyon you can go without a permit. Day-hikers were a strangely relieving sight after many solitary hours in the canyon.

Several groups lounged in the water, laughing and taking photos. Nobody seemed alarmed by the growing clouds, which over the last few miles had developed into ominous dark-gray waves that covered the canyon behind us, accented by strong gusts of wind.

The unmistakable “a storm is coming” kind of wind.

At this point, the worry in our group became tangible.

Behind us loomed a growing afternoon thunderhead, and ahead of us awaited Wall Street — a two mile section of vertical walled slot canyon. It’s the part of the Narrows you’ve most likely seen photos of. Huge, dramatic walls completely devoid of high ground.

Utterly inescapable in the event of a flash flood.

As much as we’d been looking forward to the walk through the most prolific segment of canyon, the possibility of a flash flood festered in the back of all of our minds. And then, as if on cue, a deep roll of thunder bellowed from the clouds behind us.

Ohhh shit.

Immediately, the mood shifted, and everyone at Big Spring started hastily gathering their belongings.

And then, we casually overhear from a group of hikers that at 6:00am, just as we were hopping on the shuttle to head for the top of the canyon, and just after we’d checked the forecast for the last time, the National Park Service upgraded the flash flood forecast for Zion from “not expected” to “possible”.

The most spectacular section of the entire hike in an instant became the most treacherous.

We headed into Wall Street, moving over the slick river rocks and boulders as quickly as possible, when rain drops begin to fall. Big, icy cold raindrops. Lightly at first, but the situation was quickly unfolding in an unpleasant direction. I made a point to check in with everyone from our group.

“How are you doing?”

“Umm, pretty concerned, to be honest.”

“Yeah, me too. All we can do is keep going and look for high ground.”

The conversations were brief, and interrupted with booms of thunder, growing closer together every minute.

The rain came down harder. Wind ripped up the canyon in strong gusts, blinding us with water and dust. My eyes wildly scanned the canyon walls for cracks and chimneys, just in case things take a turn for the worst. I imagined scrambling up inside one as a wall of water roared down the canyon.

How long could I hold myself out of the current? Could everyone else manage to scramble into a crack as well? How high would the water get?

Every roar of thunder sounded exactly what I imagine a flash flood would sound like. Every few seconds another roll of thunder. Every few seconds a panicked and instinctual glance over my shoulder. Every few seconds a wave of relief that a wall of water isn’t chasing me.

Then the rain really picked up. Wind kicked it into horizontal sheets, slapping against the canyon walls and streaming down the sandstone faces. It became an absolute downpour, I was practically running through the river in search of high ground.

It was as if a switch flipped, and I felt a wave of pure, unadulterated, animal fear wash over my entire body. We had been in Wall Street for almost an hour, we had to be close to the end now.

Then it appeared. A fifteen foot mound of sand and boulders tucked into a corner of the canyon. One by one, our group reconvened on top of it—we’re all safe, but none of us has the canyoneering experience to know whether the ground we’re on is high enough. The driftwood wedged in the rocks around us seems to indicate it is not, but it’s the best we can do for now.

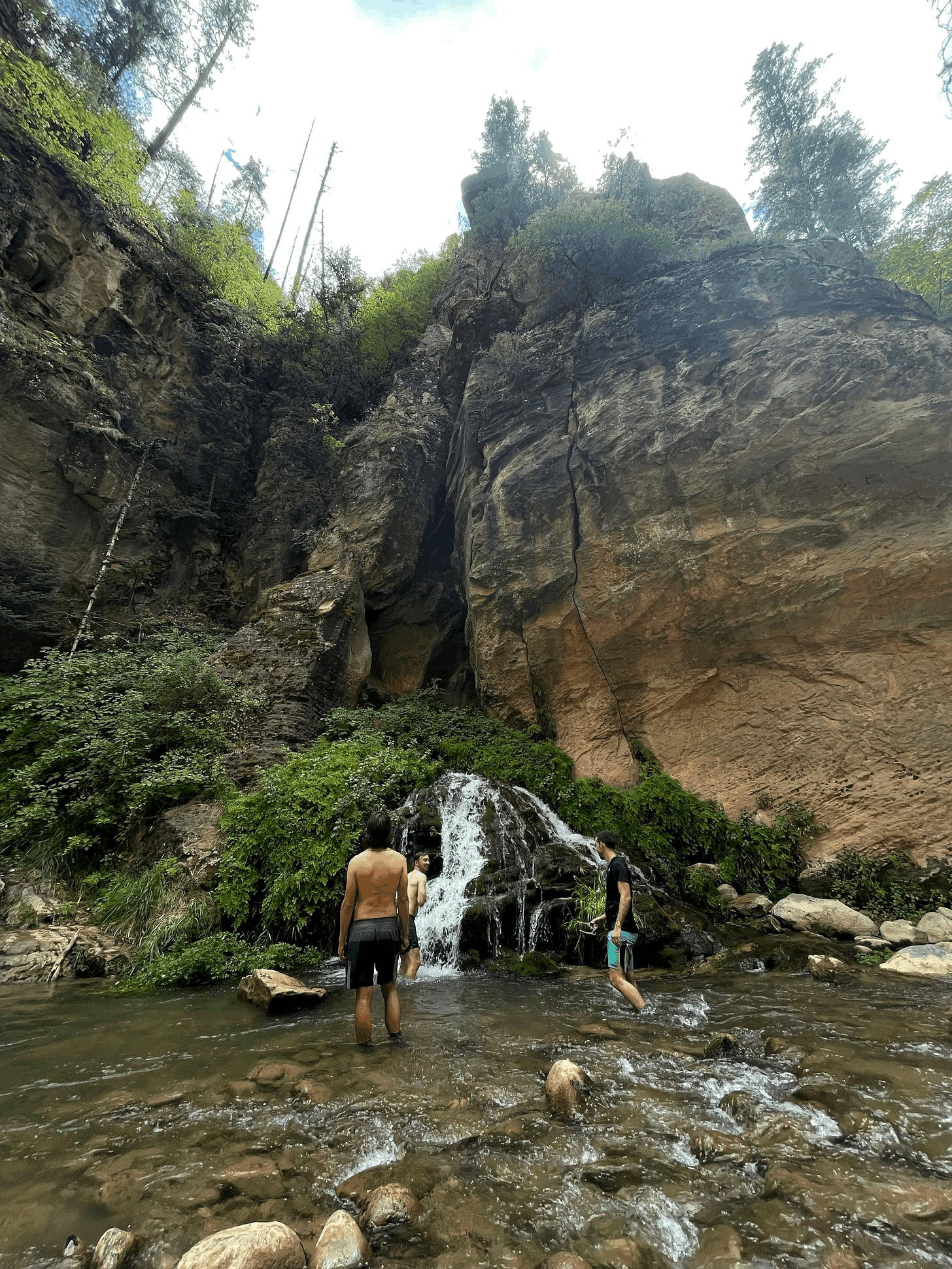

A minute later, a group of three older hikers joined us. They didn’t speak much english, but seem to be in good spirits. I flashed a questioning thumbs up to the group and the oldest responds with a smile and thumbs up in return. A family of four joined a few minutes later. The two kids must have been only seven and ten, and they’re both shivering. Luckily, we have a camp towel to share. The rain and thunder continued, and ghosts of waterfalls past came back to life, spitting their way down the canyon walls.

I grew up in church. I’ve spent many hundreds of hours talking about god, questioning god, imagining god, praying to god, and generally wondering whether god actually cares about any of these bizarre human things we’re up to.

Standing on a small patch of high ground in a tiny scratch on the surface of the globe, as rivers raged vertically down sandstone walls, as thunder reverberating through the canyon hit the resonant frequency of the earth itself and vibrated up through our feet into our chests, and as chemicals pulsed through mind and body and reflexes twitched with clarity, I am face to face with capital-G God.

This is God beyond language, beyond understanding, and beyond any delusions of human influence or control.

This is God of fear, of raging wild power — the kind of strength that needs no introduction, no sacred texts, no prayers, no pastor.

Beliefs, convictions, and ideals crumble like sand in the face of this being — this One is inevitable, and so far beyond the reach of such small human efforts to comprehend.

I made it a point to check the water level every few minutes. Even through the worst of the downpour, the water level didn’t change. None of the classic signs of a flash flood presented themselves — no floating debris, no chocolate-milk water.

I have no way of knowing how long we waited on high ground, perhaps twenty minutes, but eventually the rain stopped and the skies lightened to reveal small patches of blue again. Noting no change in the river, we collectively decided to make a move, and tentatively made our way back into the water, continuing our trek out of the Narrows.

While the threat of a flash flood still loomed, our spirits took a turn for the better and the final few miles to the mouth of the canyon were punctuated by dazzling patchworks of sunlight, fleeting momentary waterfalls, and a palpable gratitude for life.

Plus, I never did have to poop in the canyon, thank lowercase-g god.

There wasn’t a flash flood in the Narrows on July 9th. Had we known before we left cell service that the park service upgraded the flash flood warning level, we probably wouldn’t have gone for it in the first place, but the experience brought us all face-to-face with the unpredictable nature of nature.

It’s easy to forget how insignificant we actually are when we’re surrounded by so much of our own creation. Air conditioning and cars and fast food and bluetooth noise cancelling headphones. Zion National Park can feel a lot like Disneyland when you’re hopping on and off shuttle busses to hike on paved trails to well-crafted vista points. While I wouldn’t necessarily choose to spend another thunderstorm in a slot canyon, it was one of those encounters with nature—the unpaved, gritty, raw, unpredictable real nature—that is fleeting in modern life.

I took it as a stark reminder that the nature of the world is always and continuously and forever wild, powerful, and complex. Whether we’re paying attention to it or not. With some grace, perhaps I’ll be a little better equipped to pay a little more attention moving forward.

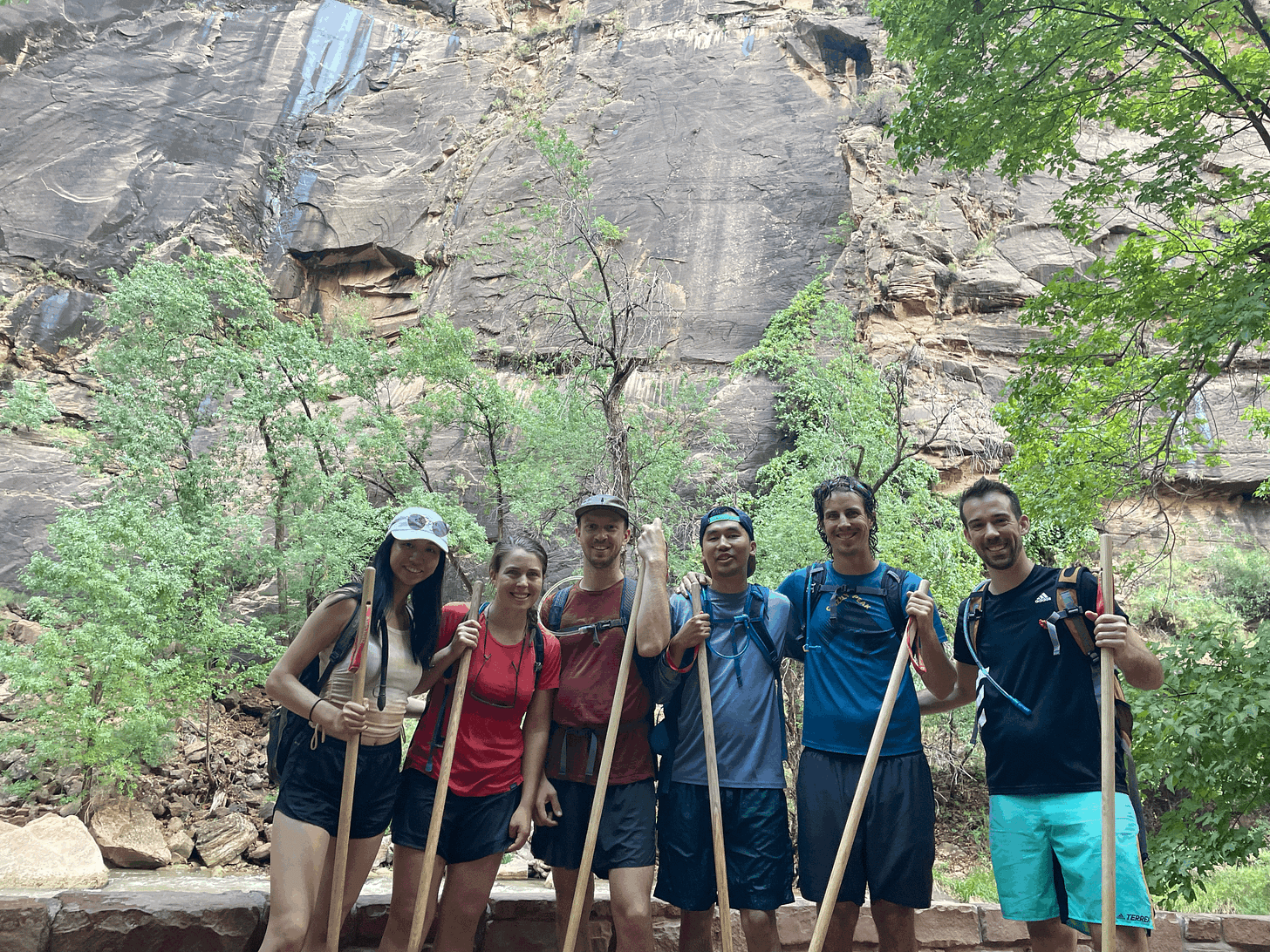

When we finally made it out the bottom of the canyon, we turned around to this: