The Salton Sea: California's Accidental Desert Lake

Years of agricultural runoff transformed the bustling 60s lakefront resort into an environmental disaster, and things only seem to be getting worse.

Did you know there’s a lake twice as big as Lake Tahoe sitting in the Sonoran Desert in Southern California? Clocking in at 343 square miles of water and over a thousand miles of shoreline, the Salton Sea is the largest lake in California and was created completely by accident.

The Salton Sea flooded into existence in 1905 when historic rainfall breached temporary dams and levees near Yuma, Arizona. Ironically, engineers were working on a network of aqueducts to get a little water into the Imperial Valley to support agriculture.

They inadvertently got a lot more water than they expected. The entire flow of the Colorado cascaded downhill into the Salton Sink for the next 18 months, wiping railroads, farms, and an entire valley community off the map. In a year and a half, what was once an arid depression in the desert became a freshwater oasis.

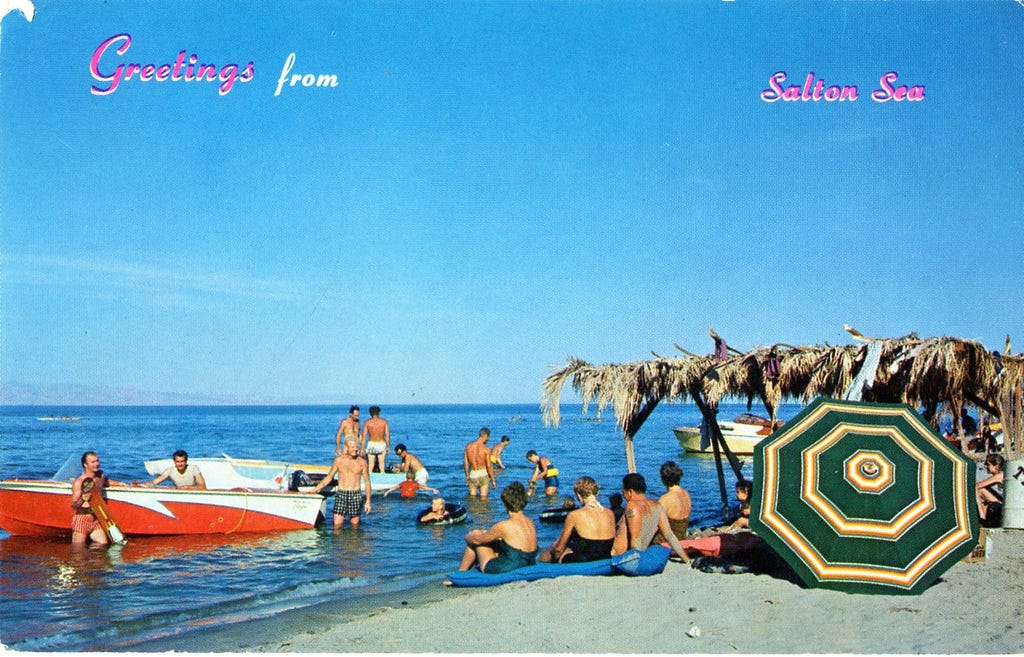

What does one do when a new lake pops up in the California desert? Build expensive resorts on it, obviously. During the 50s and 60s, developers constructed immaculate yacht clubs, hotels, restaurants and beach fronts along the shores of the Salton Sea. Families enjoyed days boating and swimming, and celebrities escaped the city for weekends at a desert oasis. In its prime, the Salton Sea attracted more visitors annually than Yosemite National Park.

The Salton Sea sits 200 feet below sea level, and therefore has no natural outlets to the ocean. This means it is essentially a giant mineral-trap. Salts and trace minerals dissolve into the incoming rivers, and as water evaporates off the surface of the lake, the salinity of the water increases.

This isn’t a completely unique phenomena, and in and of itself isn’t necessarily a bad thing. The moment the Colorado River was diverted back to its original course, however, the Salton Sea was on track for disaster. Without its main freshwater source, the Salton Sea’s remaining inlets were exclusively a mixture of agricultural and industrial runoff.

Nevertheless, for twenty years the Salton Sea was whimsically blind to its impending doom. As pesticides and toxic chemicals slowly leached into the lake, tourists kept partying in the sun. But the desert beachfront holiday was short lived. In the 70s, the first of several massive fish die-offs occurred at the Salton Sea. Thousands of dead fish covered the shores, and the smell of rotting seafood filled the entire valley for months. In turn, massive bird die-offs followed when migratory shorebirds ate the contaminated fish.

Needless to say, tourism ground to a halt. In a matter of a few years, what was once a pristine desert oasis quickly became a post-apocalyptic nightmare. In 1999, an algae bloom killed another huge portion of the remaining fish in the Salton Sea, and fish remains covered the shores for the next decade. The resorts fell into complete disrepair — the once-luxurious Bombay Beach Club is now a small grid of mobile homes and derelict art displays. Counter-culture desert communities like Slab City replaced the yacht clubs, and funky art installations like Salvation Mountain and East Jesus are today’s big tourist-draws.

Historically, lakes have existed in the Imperial Valley off and on for the last ten thousand years, periodically refilling and drying up as rivers change course and the climate shifts. The last lake in the region covered more than five times the surface area of the Salton Sea and dried up around the year 1600. In the last twenty years, the water level at the Salton Sea has dropped more than 10 feet, leaving 15,000 + acres of dry lakebed baking in the sun. The sea is on track to evaporate almost entirely by the year 2030, which is the natural course of things for a lake in the desert.

This inevitability poses a massive health crisis for communities in the Imperial Valley and beyond. As the Salton Sea evaporates, it leaves behind a lakebed contaminated with toxins that are swept up by wind, creating poisonous dust storms. This has already resulted in widespread health consequences for people living in the area. The asthma rate surrounding the Salton Sea is three times higher than the rest of the state, and selenium and arsenic in the contaminated soil lead to hair loss, cardiovascular disease, and neurological damage.

Left unchecked, the Salton Sea has the potential to become the worst air-quality disaster in the world. Ironically, the contaminated water is the only thing keeping the pesticides and chemical runoff out of the atmosphere and contained on the ground.

Despite the horrific conditions, the Salton Sea is still an essential wildlife area for plants, animals, and birds. It is one of California’s few remaining wetland ecosystems and provides a critical stopover point for migratory birds on their route from Alaska to South America. Every winter, bird watchers gather at the Salton Sea to spot great blue herons, double-crested cormorants, and the 400 species of migratory birds that stop in at the Salton Sea. The Salton Sea is also home to the largest population of American white pelicans in North America. Nearly 30,000 acres of shoreline are designated protected wetlands, and conservation efforts are underway to ensure the area remains a viable habitat for wildlife.

In a full-circle confluence of modern irony, the question up for debate today is how exactly to preserve the accidentally-created desert lake in order to avoid further ecological disaster. Some groups have proposed desalination plants, and it is clear that farming practices that use toxic fertilizers and pesticides need to change. The leading solution proposed by the Salton Sea Association (SSA), however, is to build a 125 mile canal from the Sea of Cortez to the Salton Sea — a distance twice as long as the Panama Canal. It would be the second largest water-control project in North America behind the Hoover Dam. Questions have been raised as to the practicality of this solution and, more importantly, our ability to maintain infrastructure of that scale into the future. So far, no consensus has been reached and the clock ticks away.

If history is any indicator, the Salton Sea will almost certainly disappear into the desert again in our lifetimes. Although the heyday of bustling beachfront resorts sits in the past and the threat of toxic dust-storms lay inevitably in the future, the Salton Sea seems for the moment frozen in time. A modern-day ghost town, inhabited intermittently by White Herons, Great Egrets, and Sandhill Cranes on their journey across the desert.

Hi Aaron! I love how much historic research you put into this post. As they say, to know the future, you need to know the past. I find it interesting that the lake is both a source of life and death. On one hand, it's "an essential wildlife area for plants, animals, and birds" while on the other hand, it's an air quality disaster. The situation is so nuanced, it's no wonder why people can't reach a consensus on what to do about its future.

Though I'm trying to travel the world right now, I grew up in Orange County and will always consider that area my "home". Your posts on California history and nature is somewhat comforting to read when I'm thousands of miles away from the state. Thanks for sharing these stories. :))